3. The enamel roads of antiquity

From the 11th to the 7th century, we have no relevant archaeological findings and enamelling seems to be extinct. We must wait till the 7th century BC to see a sudden reappearance of the technique in different parts of the Old World, in the form of little enamelled details on filigree-decorated gold pieces.

The reason for this sudden rebirth of enamel is unknown, but we may make some conjectures: a key role might be that of the Assyrian Empire, that reached its maximum expansion right in the 7th century BC. As for Egypt, the supposed presence of enamel proper in Mesopotamia in the form of coloured glass on jewels of this period are insufficiently solid, but there are different elements in favour of a decorative use of enamelling by the Assyrians. In this respect, this is what writes archaeologist and historian Roger Moorey: “The whole question has been reopened by finds in the royal tombs at Nimrud in 1998-9, which included elaborate gold bracelets decorated with polychrome cloisonné work. Although some parts of it are clearly inlaid with semi-precious stones, some parts might be true enamel” (source: P.R.S. Moorey, Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1994). It is noteworthy that the Assyrians mastered some techniques similar to enamelling, in particular the use of glass pastes and ceramic glazes that required identical technologies as enamelling on metal.

Amongst the indirect proofs, we can mention that, during the reign of Ashurbanipal (668-627 BC), Assyria controlled both territories where enamelling had already existed (such as Cyprus and, possibly, Egypt, as already mentioned) or that were going to use it in the next centuries. According to the historians, King Ashurbanipal was the greatest patron of art and literature of the time and this may have favoured the spreading of enamel within and without the borders of the Empire, combined with the Assyrian use to deport and mix the conquered populations.

There were probably two distinct routes of enamel in antiquity:

- The Eastern Enamel Road was due to the Scythians, an ancient Iranian population of warriors that brought enamelling through two vectors. The oldest was the Asiatic vector through the Silk Road, witnessed in the findings of Ziwiye, Azerbaijan (sources: A.H. Dietzel, Emaillierung, Springer-Verlag, 1981; R.A. Higgins, Greek and Roman Jewellery, University of California Press, 1980) and that of Arzhan, Southern Siberia, at the borders with Mongolia (source: B. Armbruster). In these findings, both dated to the 7th century BC, we can find only white enamel in a few finishes. The second vector, through the Caucasus, was much later and its witness is the 4th century BC Kul’Oba treasure in Crimea.

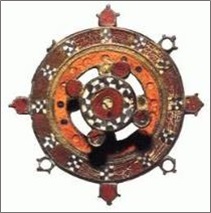

Detail from a Scythian bracelet, Kul-Oba (Crimea, Ucraine), cloisonné enamel on gold, 4th century BC.

- The Western Enamel Road, on the contrary, was due to the Phoenicians. During the rule of Ashurbanipal, while subject to Assyrian power, the Phoenician city of Tyre in present-day Lebanon controlled a huge number of mining colonies including Carthage (Tunisia), Tharros (Sardinia) and, foremost, the cities of Tartessos and Cadiz in Andalusia (Spain). In these Spanish settlements we can notice the findings of golden jewels with little enamel finishes, such as the collar of the Treasure of El Carambolo (dated to the 8th-6th centuries) and the 7th-6th century BC collar of Gadir (source: Núria López-Ribalta), both of them not too different from the corresponding Assyrian and Scythian findings of the time.

Thanks to this market in the Mediterranean Sea, between the 7th and 4th centuries, enamel achieved Etruria in present-day Tuscany and Magna Graecia in present-day Southern Italy (source: Valérie Gonzalez, Gli smalti dell’Europa musulmana e del Maghreb). The execution in these cases is so accurate that we may suppose a well-known technique. In particular, in Etruria we found some enamelled golden jewels: one of them, dated to the 6th century BC, is today in the Metropolitan Museum, while another pair of swan-shaped earrings, dated to the 3rd century BC, are part of the Campana Collection in the Louvre Museum(Paris).

Etruscan earring, cloisonné enamel, 6th century BC

Dove-shaped Greek earrings from Milos, filigree enamel, 2nd century BC

A separate case is that of the Celts, who showed the practice to enamel bronze objects of different kinds with a vivid red colour since at least the La Tène period (5th century BC), while in the British islands enamel developed during the 3rd century BC. In this case, the technique was completely original, in the form of champlevé on engravings in the cast bronze. They will continue to practice this technique for many centuries. The mysterious origins of the Celts make it difficult to propose a definite theory on the origin of their enamel knowledge, but the hypothesis of a Caucasian homeland may link the Celtic enamelwork to the Scythian technique through the Eastern Enamel Road (for more information, please read our article "The Celts: unknown masters of ancient enamelling and rulers of Europe").

On the left: the Battersea Shield, repoussé bronze with champlevé enamels, 2nd-1st century BC. On the right: A detail of the red opaque enamels.

A territory of great fertility for the production of enamel jewels is Nubia, in present-day Sudan. Excluding a few fragments of enamelled metal dated to about 600 BC, of possible Egyptian or Mediterranean origin, it is in the Meroitic period (270 BC – 50 AD) that enamelling emerged as a national art. At this time that the local goldsmiths experimented with the champlevé technique and the earliest attempts at translucent enamel (Y.J. Markowitz, D. Doxey, Jewels of Ancient Nubia, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2014).

Bracelet from the treasure of Queen Amanishakheto, Nubia, cloisonné enamel, 35-20 BC.

Between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, the Romans used the enamelling technique mainly for the decoration of daggers and scabbards used by the Roman army; it is in Rome, under the empire of Octavian Augustus, that a production of millefiori glass flourishes. With the expansion of their empire, the Romans spread enamelled objects of different origins and functions, such as fibulae and claps. There was the birth of a hybrid Gallic-Roman style of champlevé on cast bronze with a somewhat rough technique, we might say barbarized. The findings of medieval objects with compositions identical to those of Roman millefiori glass have revealed that the enamels from Ancient Rome have been recycled in medieval times for the creation of new works after the conversion of the Empire to Christendom, thus explaining the apparent lack of findings in the Imperial period. This is the same destiny as that of other construction materials of the time. We will deal with this phenomenon and its documentary and chemical proofs a propos of enamel in the Middle Age.

Roman fibula, bronze and champlevé enamel, Vaison-La-Romaine, 3rd century AD.

The archaeological digs in Britain during the Roman occupation period demonstrate that, before the arrival of enamelling, the British craftsmen decorated their bronze items with red coral inlays, that were replaced with red opaque glass over time. It seems, indeed, that red was quite widespread, as we said, in the Barbarian and Celtic civilizations. By the end of the 1st and beginning of the 2nd century AD, it is possible to find several little objects, decorated initially with red enamel and later with different colours, mainly yellow, blue, green, black and white. The most common enamelled items were brooches, studs and harness equipment with little enamel bronze decorations. It is not possible to state with certainty whether there was a local enamelling manufacture or if the works were imported, although it appears probable at least in for a few sites in Britain, such as Traprain Law (Scotland), Dinas Powys (Wales) and Colchester (England). A given fact is that the raw materials used in enamelling were the same as those used in continental Europe (source: Frances McIntosh, A Study into Romano-British enamelling with a particular focus on brooches, 2009). Alongside the little enamelled pieces, there are also a few larger objects, especially houseware made of bronze or copper alloy, such as the 2nd century AD "Ilam Pan" or Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, found on the boundary of Hadrian's Wall.

Staffordshire Moorlands Pan, Britain, champlevé on bronze, 2nd century AD